By Michael and Barbara Foster

Authors of A Dangerous Woman: The Life, Loves and Scandals of Adah Isaacs Menken–America’s Original Superstar (Lyons Press 2011)

and least. This year’s event, the 84th, is particularly fraught with ghosts, most sadly that of Whitney Houston, but in a lighter vein that of Marilyn Monroe, played by nominee Michelle Williams in My Week With Marilyn. Viola Davis in The Help reminds us of the Civil Rights struggles of the sixties, and Meryl Streep re-enacts the reign of Margaret Thatcher in the UK during the eighties. Perhaps the most notable ghost is the Eastman Kodak company, the now-bankrupt sponsor of the Kodak Theatre.

Watching the Sunday evening show on TV we’ll see daring gowns, plenty of skin, sexiness, and talent on display, and the golden glow of those little statues as they are doled out to the winners. We’ll hear Billy Crystal crack jokes and Tina Fey present, so there will be plenty of laughs on Hollywood’s biggest night. But for now, let’s step back in time to the original star, to the magic symbiosis of sex and danger that makes for major movies, and to the first power couple’s marriage followed by the almost inevitable front-page scandal. Let’s look at the ghosts of fallen stars.

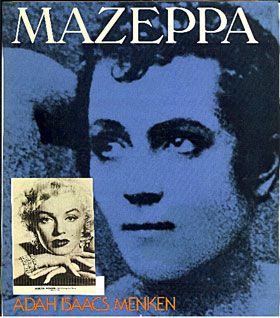

Broadway–the Great White Way–and later Hollywood–began in Albany, New York on June 3, 1861. That night the audience at the Green Street theater gasped as Adah Isaacs Menken catapulted to the theatrical heavens on the back of a wild steed. Mazeppa, a drama in which she played a freedom fighting prince, brought Adah instant super-stardom. On opening night, savvy impresario John Smith placed his money on the curvy, violet-eyed beauty whose scandalous personal life kept the popular, two-penny newspapers in copy. Born into poverty in New Orleans in 1835, part-Black, Jewish, and Irish, Adah in her mid-twenties had gone through three husbands, with two more to go. Her latest marriage to boxing champ John Heenan, America’s first great sports hero, proved a disaster. The glamorous couple divorced, a highly public spectacle that dominated the media of its day: the tabloids, the telegraph (Twitter equivalent), and newly invented photography.

In court, Heenan called his ex-wife “the most dangerous woman in the world,” from which we borrowed the title of our biography, A Dangerous Woman. Adah Menken was on her way to becoming the most desired woman in the world. In her cross-dressing, or rather undressing, role in Mazeppa, she appeared stark naked to the audience, though she wore a sheer, pink bodystocking. Captured by the enemy, Adah was tied to a horse and sent up the ramps of a four-story stage mountain to perish in the wilds. The nudity was an illusion–similarly, a model was painted nude in a 2012 Superbowl ad–but the danger of death from an accident was real. Fort Sumter had fallen to the Confederacy, the Civil War was on, and troops North and South pinned photos of Adah, the more bare the better, to their tent poles or knapsacks. Adah, The Naked lady, was admired across the lines. The Love Goddess in time of war was born, a role later played by Betty Grable during WW II and Marilyn Monroe during the Cold War.

Adah Isaacs Menken

Adah’s audacity caused the puritanical Horace Greeley, publisher of the influential Tribune and presidential hopeful, to fume. His paper refused to carry advertisements for contraceptives and virility aids, and now Greeley blasted Menken for daring to bare her body in public. He was equally outraged that she usurped the role of a male warrior, and in the battle scenes soundly whipped her opponents. Sounds like certain presidential candidates today, who are against birth control and women in combat. American prudery dies hard.

Predictably, there was no such thing as bad publicity. In the midst of the war, Adah toured the country by train and steamship, packing theaters from Broadway to Gold Rush California and cities in-between, sometimes to the sound of canon fire from the front. Adah’s manager Ed James, editor on The Clipper, the Variety of its time, called the first known theatrical press conference. His fellow journalists gaped at the beauty whose star quality struck them like a bolt of lightning. That she bobbed her hair, smoked cigarillos, and wore pants in public made for great copy. In San Francisco, cub reporter Sam Clemens (later Mark Twain) compared Adah’s effect on the populace to a constellation of stars flaming out of the heavens, which he dubbed “the Great Bare.” Thanks, Sam, for the name of our website: TheGreatBare.com

From “the frenzy of ‘Frisco,” Adah steamed across two oceans to become the darling of Victorian London and the toast of Imperial Paris. Mazeppa packed the theaters, and afterwards Adah’s soirees were attended by her friends and lovers, including aristocrats, artists and actors successful and hungry, Dickens, Tennyson, Swinburne, George Sand, Alexandre Dumas pere, and defeated Confederate generals and spies. The French Emperor Napoleon III tried but failed to seduce Adah, but her affair with Dumas caused an international scandal when intimate photos of the pair were widely distributed. In Paris La Menken lived high and performed higher, and at one performance the inevitable happened: horse and rider fell from grace.

In August 1868 Adah, thirty-three, lay dying in a modest Left Bank hotel. She had literally thrown away her money to the poor in the streets. A crowd at a nearby theatre demanded to see the latest Naked Lady show. At Adah’s bedside Henry Longfellow wrote her a last love poem. A Jewish rabbi attended her, and Adah, barely conscious, was able to follow the Hebrew prayers. Dumas, the old Musketeer, on hearing that Adah had passed away, remarked, “Poor girl, why was she not her own friend?”

We may ask the same question about Adah’s spiritual descendants, such as Jean Harlow, Marilyn Monroe, Princess Diana, and Whitney Houston. Beautiful women, talented superstars, each was her own worst enemy. They performed brilliantly, the world worshipped them,

Adah Menken lives on in many ways. Her roles and poses and spirit were captured in incandescent images by Napoleon Sarony, the first star photographer in the infancy of the craft. Here we find Adah at her most dramatic, or in a bodystocking, most provocative. The Naked Lady anticipated the “less is more” of models and celebrities on today’s magazine covers. And there have been stars playing Menken in the movies: Sophia Loren played a character based closely on Adah in Heller In Pink Tights, George Cukor’s only Western. Adah’s many admirers included Arthur Conan Doyle, and the character of Irene Adler in the recent Sherlock Holmes is another Adah Menken knock-off. “To Holmes,” says Dr. Watson, “she was always the woman.”

To the Falling Stars, we paraphrase Whitney Houston’s iconic line: We will always love you.

About Michael & Barbara Foster

Michael Foster is a historian, novelist and biographer, acclaimed by the New York Times. He earned his Master of Fine Arts from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. A Dangerous Woman is his fifth book. Barbara Foster is an associate professor of women’s studies at City University of New York. www.thegreatbare.com