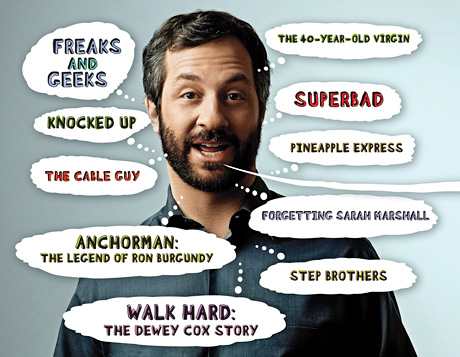

What would the Hollywood comedy scene be like today without such iconic figures as Ron Burgundy, the ‘40 Year Old Virgin’, and the legendary ‘Superbad’ duo? With two new films coming out this summer, Year One and Funny People, the writer, producer and/or director of almost every modern funny film, Judd Apatow, is a person everyone is dying to know. In a recent Playboy interview by Eric Spitznagel, Apatow reveals insider information about his life, including his unusual taste for male anatomy, his unique relationships with Adam Sandler and Seth Rogen, and the real reason why weeping male characters are a trademark of his films.

APATOW: No. Luckily that part of the movie is all from my imagination. I can say with full confidence that I’m not dying from a rare blood disorder. I had always wanted to make a movie about the relationship between two comics. The problem was I didn’t have a great story. Nobody wants to watch a two-hour movie about a hilarious older comic being kind to a young man. That’s just a terrible idea. But then it turned into a demented-mentor movie with a father-son aspect. I find that fascinating.

P: Your characters suffer through failed marriages, fractured relationships, the slow conviction that everything they’ve done is crap and, eventually, dying young. Is that what success as a comedian means to you?

A: There’s a fine line between what’s healthy about being a comedian and what’s sick and twisted about it. When I’m doing good work, a part of me feels as though it’s a contribution to society. I’m making people laugh and helping them think about their lives in a positive and life-affirming way. At the same time, a sick, wounded part of me just wants to know somebody out there likes me. I serve both gods simultaneously.

P:Â How is making a comedy film different from being in therapy?

A: It’s different because you don’t have a therapist to interpret your babblings for you. Just before I started shooting Funny People I stopped going to therapy. And now that I’ve finished the movie I have this weird instinct to avoid going back. I think it’s my responsibility to work through all the issues the movie raised for me. In a weird way, it seems as though talking about it with a therapist would be cheating.

P:Â Men cry a lot in your movies. Are you a naturally weepy sort?

A: Absolutely. I’m a big crier. Sometimes when my wife and I are watching a movie we’ll both start to cry at the same time, and then we’ll slowly turn toward each other to acknowledge that it got both of us. That’s great and funny when we’re both crying, but it’s not so wonderful when I’m the only one in tears.

P: Your movies are so popular your first name has become a verb: “Judd it up†has become a familiar refrain on Hollywood movie sets. Is it humbling to realize you’ve spawned your own comedy genre?

A: I don’t think I’m doing anything particularly different or original. There’s nothing new about comedies about underdogs who make an enormous number of mistakes and learn from them. That goes back to Buster Keaton. We’re just doing our generation’s version of Buster Keaton.

P:Â When you were growing up, you used to transcribe Saturday Night Live scenes. In hindsight, was that time well spent?

A: Back when I was watching Saturday Night Live for the first time, VCRs hadn’t been invented yet. So whenever the show aired, I thought to myself, If I don’t watch this now, I may never get to see it again for the rest of my life! I would put a tape recorder right next to the TV, and then I’d sit up all night and transcribe the skits that amused me the most. I don’t know why I did it. I did the same thing with Twilight Zone episodes.

P: As a teenager, you interviewed dozens of your comedy idols, including Garry Shandling and Jerry Seinfeld, for a high school radio station. Did you ever listen to any of them and think, I’m a thousand times funnier than this guy?

A: Not really. I always tried to interview people I respected. Some were nicer than others. Some of them taught me lessons that proved to be invaluable. When I interviewed Seinfeld, he said, “It takes seven years to find your voice as a stand-up comic.†So when I started doing stand-up, I didn’t think I was awesome after being onstage just a few years. It gave me a patience I wouldn’t have had otherwise.

P: After your first two network TV shows—Freaks and Geeks and Undeclared—were canceled, you sent an angry letter to the responsible TV executive, wondering how “can you fuck me in the ass when your dick is still in there from last time.†Has time healed all wounds, or is his penis still in you, figuratively speaking?

A: Nothing is more painful than being canceled. But sometimes it just ends out of nowhere and everyone has to go home. I tend to take cancellation particularly hard: I cry, I have back surgeries, and I’m bitter for decades.

P:Â Do you ever attempt to get revenge?

A: I go so far as to attempt to turn every single person who ever acted on any show I’ve ever been involved with into a feature-film star just so I can prove I was right about the TV show. Sometimes the actors will say to me, “Wow, you must really think I’m good.†No, I don’t think you’re good at all. I just have to prove to that goddamn TV executive that he made a mistake. It’s not a sign of my support; it’s a sign of how insane I am. I’m the most arrogant man on earth, and I always need to be right.

P:Â From Freaks and Geeks to Funny People, you and Seth Rogen have been collaborating for more than a decade. At what point do the two of you become common-law spouses?

A: I don’t know if we should be married or if I should become his adoptive grandfather. Seth has said he thinks of me as his creepy uncle. [laughs] I like that.

P: You and Adam Sandler, who co-stars in Funny People, were roommates in the early 1990s. Was that an Odd Couple–type relationship?A: We had a good time together. It was a $900-a-month apartment. I paid $425, and he paid $475 because he had a bathroom in his bedroom. I had to use the guest bathroom. Most days we would sleep till noon, get up, eat, spend way too much time in a mall, do stand-up-comedy sets at the Improv and then eat again at 1:30 in the morning.

P:Â While you were roommates, Sandler purportedly demanded to see your penis. Did he ever bother to explain why?

A: He used to say, “I just want to know what I’m dealing with.†That was his only explanation. On some deeply macho level, I understood.

P:Â Seth Rogen told Playboy you made some pretty bold claims about your penis. Apparently it has gray pubes, looks very distinguished and could teach a Harvard class in literature. Do you stand by that description?

A: It’s a complete fabrication. I use Grecian Formula now. It still looks distinguished. From a certain angle it kind of looks like Ben Kingsley.

P:Â Many of your movies feature male nudity. Why are penises so funny?

A: Because a penis looks like a man with a big nose and large ears. [laughs] It’s a vulnerable area, so it’s good for comedy. But you have to be very careful about how much you show. I learned this from working on Forgetting Sarah Marshall, in which Jason Segel is naked for an entire scene.

P:Â How much is too much?

A: When you show a movie with full-frontal nudity to a test audience, you instantly learn how many seconds of screen time results in how many audience members walking out of the theater. You may get away with three seconds of penis exposure, but at five seconds you’ll lose 18 people. At 10 seconds it could be a hundred. The fear of the penis in modern society is unparalleled.

P:Â If you take out the cursing and the male genitals, your movies have traditional pro-family values. Do you consider yourself a closet conservative?

A: I never think of my movies in those terms. I just try to tell stories that have some sort of positive idea behind them. Like in Knocked Up I don’t think it’s a big leap to suggest it may be a good thing not to run away when you get somebody pregnant. I don’t think my values are so shocking. My movies depict a lot of immature behavior, but it’s usually to point out how wrong it is and show somebody on a path to finding a better way.

P: Abortion is dismissed in Knocked Up. In fact, the word isn’t even spoken. It’s called “smushmortion.†Is it safe to assume you’re pro-life, or anti-smushmortion?

A: If Katherine Heigl’s character had an abortion, the movie would have been only 11 minutes long, so that wasn’t an option for us. What interested me was making a movie about two people who don’t know each other well but decide the right thing to do in their situation is to get to know each other, just to see if a relationship can form. The baby is coming, and if nothing else, they can tell their child someday that at least they tried. That was a more interesting premise to me than anything having to do with pro-life or pro-choice.

P:Â You brought along your nine-yearold daughter, Maude, to record the DVD commentary on Superbad. Is it fair to say your daughters are pretty much corrupted?

A: My kids haven’t seen any of my movies except You Don’t Mess With the Zohan and Heavyweights. Maude is 11 now, so I probably live in a fantasyland where I still believe she hasn’t snuck behind my back and watched them herself at two in the morning on her computer. That may be why she’s not begging me to see them. If she were smart, she’d beg a little more just to make it look as if she hasn’t seen them already.

P:Â You co-wrote and directed The 40-Year- Old Virgin. How did you lose your virginity?

A: When I lost my virginity, I said to the girl, “Hey, was it good for you, too?†And she said, “Well, I guess it’ll get better eventually.†Sadly, she wasn’t right. It wasn’t better for her or any of the women who subsequently agreed to sleep with me.

P:Â Has success mellowed you, or do you still have the fierce ambition of a young filmmaker with something to prove?

A: I know what it feels like to have your movie bomb. I know what it feels like to have your movie bomb even though you think it’s really good. I know what it’s like to have your movie bomb when you know it’s not very good. I know what it’s like to succeed with a movie you’re proud of. I know what it’s like to succeed with a movie even you don’t think is very good. I’ve been through all the permutations. After everything that has happened to me, I feel I can relax and take a deep breath. But as I get older, I realize nothing has really changed. The second I finish a movie, I always want to occupy my head with a new problem, a new project. If I were truly mature, I probably wouldn’t feel the obsessive need to keep making more and more movies. I would just smell a leaf for a few years and be satisfied.

Interview courtesy of Playboy. To view the interview as it originally appeared, visit Playboy here.